Cowper’s Cut 391: The phony war of NHS reform

You won’t catch me pretending that this past week has been one of the more consequential or event-filled ones in English health policy and politics: most of us have probably had busier hairstyles.

Any sense of urgency about NHS improvement is notable by its absence.

This is concerning, because England’s health system is not in fantastic shape.

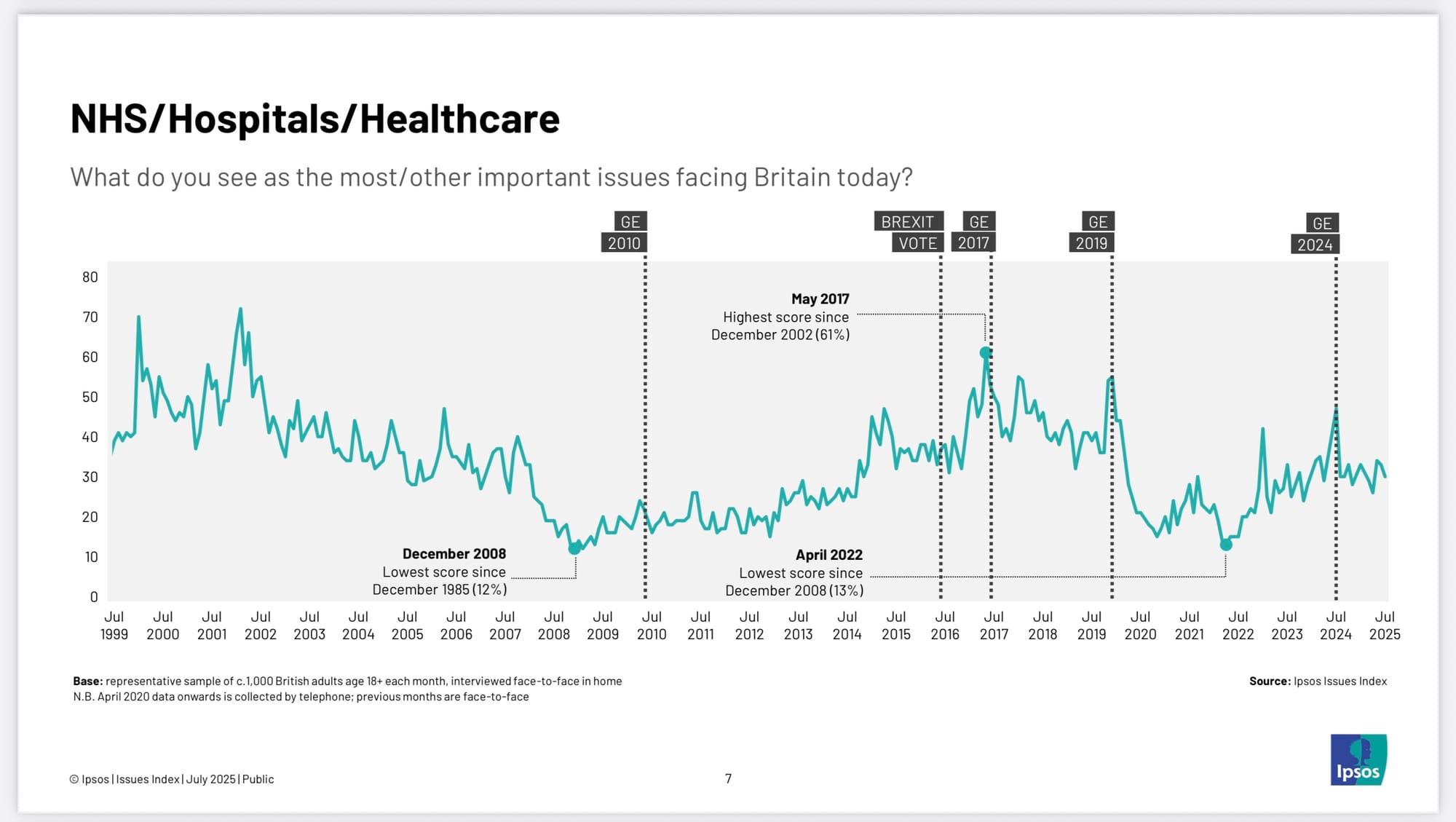

Public concerns about the state of the NHS keep it in the ‘top three’ of the long-running Ipsos Issues Index opinion polling, just edged out of its fairly usual ‘top two’ slot by rising concerns about immigration. The results of the latest British Social Attitudes survey health questions reinforce our sense of the public’s concerns about the state of the NHS.

RTT waiting list reductions seem to have more or less stalled, despite the emphasis and financial incentives being put on provider validation exercises. And getting back to 18 weeks RTT by 2029 is the manifesto commitment that the Labour government set itself.

It’s also understandable. The massive missed opportunity that was The NHS Ten-Year Plan (in reality, The NHS Ten-Year Intention) created a widespread sense of drift. Sir James Mackey and his team are trying valiantly to re-establish control and leadership of the English NHS (Health Service Journal’s Alison Moore spotted the new leadership’s attempts to get ahead of the junior doctors’ dispute), while NHS England itself is to be abolished-cum-merged into the Department For Health But Social Care. Meanwhile, local Integrated Care Systems face huge cuts.

Structural redisorganisation of English NHS management systems may be a diverting Whitehall Village parlour game, but it will not obviously address ‘The NHS Productivity Puzzle’, as accurately analysed by Sam Freedman and Rachel Woolf for the Institute For Government back in June 2023.

Indeed the relatively worse performance of the NHS in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - all of which have had largely stable management structures, as well as Barnett Formula higher per capita funding levels - may imply that management structures and systems are not a key part of the problem.

So I was underwhelmed by aspects of this new commentary by Dr Agnes Arnold-Foster and Hugh Alderwick for the Health Foundation. In ‘Bringing NHS England Back Under Closer Political Control: Lessons From History’, they argue that “in bringing NHS England back into the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), national policymakers should maintain some split between policy and management at the top of the NHS, clarify the relationship between central and local decision making and develop other routes to inject independence into the policy process”.

Um.

Well.

It isn’t clear to me that these aspirations for the outcomes of reform are based on solid description of the current and recently past situations for the management and politics of the English NHS. (It isn’t even clear to me that they are durably probable, or even possible.)

The piece makes particularly questionable statements that the creation of an arms’ length independent quango in the NHS Commissioning Board (later rebranded as NHS England) “did not work as intended. NHS England operated more like the headquarters for NHS strategy under Simon Stevens, its longest serving chief executive, and the service never freed itself from political control. The size and responsibilities of NHS England also grew over time as it absorbed other arm’s-length bodies created under the 2012 act, resulting in fragmentation and duplication at the top of the NHS.

“ … an end to political interference in the NHS did not happen. Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for six years from 2012, was at times as closely involved in the details of NHS performance and planning as any of his predecessors (for instance, directly calling up chief executives of poor performing NHS trusts).

“And in a strange role reversal, Simon Stevens, NHS England’s longest serving chief executive, took control of NHS strategy. His Five Year Forward View in 2014 effectively sidelined Lansley’s ‘choice and competition’ agenda in favour of the closer integration of planning and services that led eventually to today’s integrated care boards”.

Um.

Well.

There is a lot to unpack here.

Andrew Lansley’s clearly stated aim was to significantly restrict the Health Secretary’s direct powers over the English NHS. Dear Old Lord Lansley’s touching faith in the triumvirate powers of choice, competition and clinical commissioning to drive NHS reform seemed misplaced even at that time, but he was clearly right that for the NHSCB to have more real power, the SOS had to have less.

A big part of the flaws in the HF analysis is the failure to differentiate between the first three leaders of NHSCB/NHSE.

History has thus far under-rated the importance of Sir David Nicholson’s mix of NHS command-and-control savvy and political shrewdness to the initial viability of the NHS Commissioning Board.

At that same time, Nicholson himself publicly stated in his speech to the NHS Confederation annual conference that although he was of a generation of NHS leaders whose careers were built on “delivering our numbers”, he also knew that this old-school JDFI Approach was time-expired: the more so since Commons Health Select Committee chair Stephen Darrell smartly hung the tag of “The Nicholson Challenge” of doing without £20 billion of Wanless-projected NHS funding growth around Sir David’s neck.

Unlike many other NHS efficiency gains, The Nicholson Challenge was pretty much achieved, albeit largely by holding down national pay rates, the consequences of which we are now seeing.

Where Nicholson had significant political savvy, his successor Simon Stevens was a political weathermaker. His early NHS management career was supplemented with his time as a very political health policy advisor to Frank Dobson, Alan Milburn and ultimately PM Tony Blair; then followed by his time working for UnitedHealth, initially in the UK and Europe and then in the USA.

In 2013-14, Stevens was persuaded to return to take the top job at the NHS Commissioning Board (which he promptly rebadged ‘NHS England’, tellingly some years ahead of its legislative name-change) by the combined imploring of Coalition PM David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne, in the wake of the catastrophic politics of legislating for the Lansley reforms.

Having kept a strong watching brief on the scene (and quietly canvassed his UK health policy contacts about the chances of success), Stevens returned to quietly remodel the NHS Commissioning Board into an almost completely Stevens-centric powerbase. He was, wisely, not going to take on the accountability and responsibility for this major national institution without being able to absolutely and unquestionably dominate its running.

The authors’ suggestion that Stevens was somehow just making strategy while Jeremy Hunt intervened non-stop is, to put it politely, ahistorical. It might accurately describe a fairly brief period in the wake of Hunt’s successful facing-down of the appallingly-run junior doctors protests over their new contract, when Hunt’s interventionist tendencies, going unchecked, led him to drive the sacking of some provider chief executives. In broader terms, the famous ‘Monday morning meetings’ in SOS Hunt’s Richmond House office were a mixture of the performative and the placatory.

The English NHS was under broad political control during Simon Stevens’ tenure as its chief executive, but the politician in question was Simon Stevens. Now we might argue that this was rather a democratic aberration, but it was the reality of that situation.

As I was in the top one of commentators to notice and state on its launch in 2014, Stevens’ Five-Year Forward View was a subtle yet total subversion of the entire intellectual basis of the Lansley reforms. That 2014 analysis of mine is now widely accepted thinking (including by the authors of this piece): curiously, it was not widely admitted for several years afterwards.

The only person who thinks the NHS is in need of more Matt Hancock, is Matt Hancock... pic.twitter.com/uoenHSGylo

— Dr Murphy (aka David Watkins) (@DrMurphy11) February 11, 2021

When I published the leak of the ‘more Matt Hancock’ proposed legislation in February 2021, I wrote in my analysis that “it unambiguously puts the Secretary Of State For Health back in charge, in a massive political land-grab.

“This is in charge of both the overall system; of each local Integrated Care Systems; and of the NHS Commissioning Board (known now as NHS England).

“The Secretary Of State resumes formal powers of direction: for the SOS to have more power in this way, the chief executive of NHS England must of course have less. Ministers get new powers to intervene at any point of an NHS reconfiguration process, with a new process for reconfiguration that will enable the Secretary of State to intervene earlier and enable speedier local decision-making.

“The SOS gets new powers to transfer functions to and from specified arms-length bodies (ALBs), and the ability to abolish ALBs as a result of doing so. These power to transfer functions and abolish ALBs will be exercisable via a Statutory Instrument (SI) following formal consultation. The Secretary Of State’s revived powers of direction include the ability to mandate NHS England to take on public health functions (which were transferred to local government by the 2012 Act) without annual section 7A agreements”.

It was obvious that Simon Stevens was not going to carry on under such an arrangement, and indeed the news of his departure was not far behind.

Then there was Amanda Pritchard’s tenure in charge, and we know how well that one went.

The piece also highlights NICE as being a successful model of independent national health-related body, without mentioning how PM David Cameron’s Cancer Drugs Fund undermined the living hell out of NICE. And the latest lobbying by the pharmaceutical industry to get the NHS to pay more for drugs is bringing NICE right back into the spotlight, as its departing chief executive tells Shaun in the Sunday Times.

Recommended and required reading

I forgot to include this decent Financial Times ‘Political Fix’ discussion on the mess in the NHS, which appeared last week, so here it is now.

Not health-specific, but very good: seven public policy rules of thumb.

Nuffield Trust piece on international lessons over having assisted dying in health systems.

Kings Fund analysis on why the NHS is reliant on beds in the independent sector for mental health care.